It seems to be an annual question. Do I add ammonium sulfate (AMS) to glyphosate? Will it improve weed control especially if my water source is hard? The short answer is no. Skeptical? I understand.

There are many areas within the United States that insist the addition of ammonium sulfate (AMS) to glyphosate is critical, particularly for the control of lambs-quarters and velvetleaf. It has been well documented that certain cations in hard water can antagonize glyphosate activity (eg Ca++). This antagonism may result from the formation of glyphosate salts of low solubility. These salts are not taken up as readily by the plant, and therefore weed control may be reduced. Growers in the United States will add AMS to glyphosate as a cost-effective way of overcoming this antagonism, as AMS hinders the formation of low soluble glyphosate salts.

Sources of Cations

Hard water is the most common source of cations. However plant tissue can also produce antagonistic cations that leach onto the leaf surface when dew or rainfall wets the leaves. This may explain why the addition of AMS to glyphosate has improved control of certain weed species even when glyphosate is mixed with de-ionized water.

A study by Gavin Hall and colleagues (2000) looked at the composition of cations on the leaf surface of velvetleaf, field bindweed, and johnson grass. Control of these weeds was evaluated when applying glyphosate with and without the addition of AMS. Their results found that the greatest response in control from the addition of AMS to glyphosate was seen on velvetleaf, followed by field bindweed. There was little difference in the response of johnson grass to treatments of glyphosate with and without AMS. The response to AMS mirrored the relative concentrations of calcium within the foliar tissue as velvetleaf contained the highest concentration of Ca++ followed by field bindweed and johnson grass. Results from the Hall study suggest that calcium on the leaf surface and within the plant tissue can antagonise glyphosate activity.

The Ontario Experience

One of the first projects I worked on when I started with the Ministry was a series of field scale demonstrations where farmers with velvetleaf as a target weed agreed to spray half their field with glyphosate, re-fill the sprayer with water, condition with ammonium sulfate and then add the same rate of glyphosate to treat the rest of the field. In every demonstration conducted, the farmer did not notice a difference in velvetleaf control between the two areas of the field.

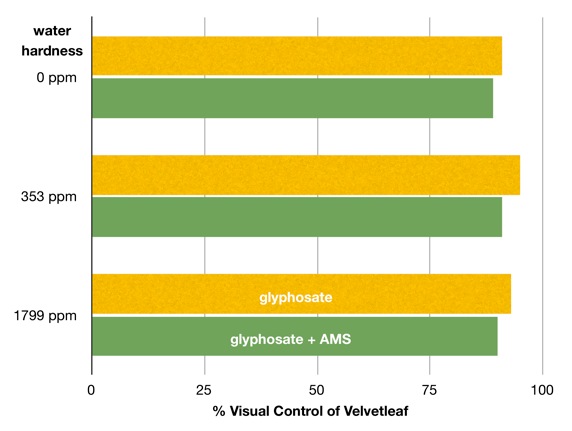

In 2011, a study by Ontario researchers concluded that in their experience “water hardness and AMS had little benefit on the efficacy of glyphosate in corn”. The two charts below have been adapted from this study to show the difference in weed control by glyphosate with and without ammonium sulfate to condition three levels of water hardness.

Figure 1. Control of lambsquarters 28 days applications with glyphosate and glyphosate + ammonium sulfate at three levels of water hardness. Adapted from Soltani et al., 2011. Can. J. Plant Sci. 91: 1053–1059.

Figure 2. Control of velvetleaf 28 days applications with glyphosate and glyphosate + ammonium sulfate at three levels of water hardness. Adapted from Soltani et al., 2011. Can. J. Plant Sci. 91: 1053–1059.

Situations where it may warrant a look

A quick google search will yield you no shortage of articles on the value of adding AMS to glyphosate, so I can appreciate why you may view this article with some skepticism. A really good resource on understanding glyphosate to increase performance can be found here.

If you want to evaluate the conditioning of water with AMS, you may see benefits when:

- You are using spray water that is very hard.

- You are targeting weeds that are known to have leaves that are “Cation rich” like lambsquarter and velvetleaf.

- You use glyphosate products that aren’t “fully loaded” (e.g. premium brands)