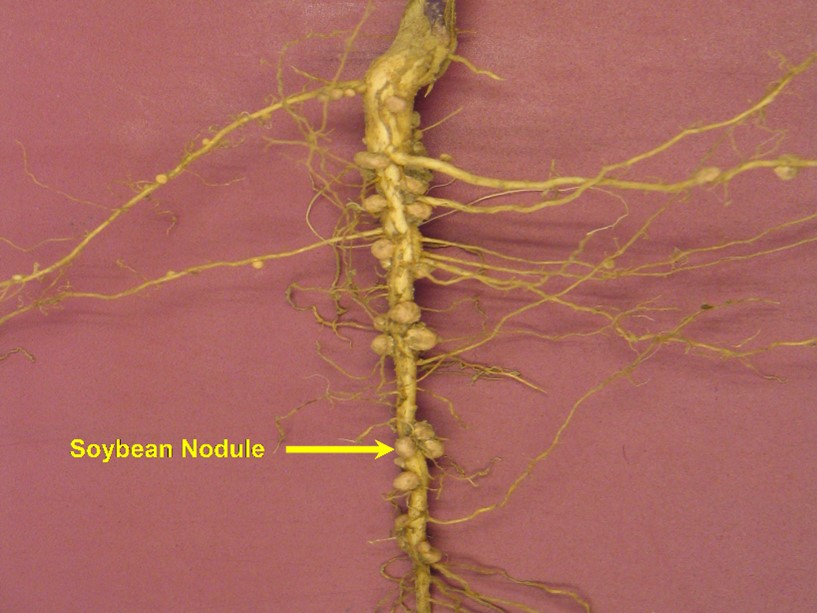

Biological N fixation

Biological N fixation converts gaseous nitrogen in the air (N2) to a form of nitrogen the plant can use, known as ammonium (NH4+). In legumes, symbiotic nitrogen fixation occurs when rhizobia invade the root hair and form a nodule on the root, see figure 1, Soybean Nodules. Rhizobia are a specific group of soil bacteria that infect the roots of legumes to form nodules. Different legumes species require specific rhizobia to ensure effective nitrogen fixation. In this symbiotic relationship the rhizobia receive a protected growing environment, carbohydrates, and minerals from the plant. The plant is provided with nitrogen by the rhizobia. A 3.4 t/ha (50 bu/acre) crop of soybeans will take up over 230 kg/ha (205 lb/acre) of N. Some of this N comes from the residual nitrogen in the soil, but 50%-75% will come from biological N fixation. The amount of N that comes from the soil depends on home much is naturally available in the soil and environmental conditions such as temperature and moisture.

Figure 1. Soybean Nodules. Rhizobium nodules formed by Bradyrhizobium japonicum on a soybean root.

Nodule formation and inoculation

The process of adding soybean rhizobia (Bradyrhizobium japonicum) to the soil is called “inoculation”. This is often accomplished by adding the inoculant to the seed, but liquid or granular soil application is also possible. Shortly after soybean emergence, the roots become infected with the rhizobia. Nodules may be observed as early as a few weeks after planting. On first-time soybean fields, nodules will be located mainly on the taproot, but in fields with a history of soybeans, nodules will also be found along lateral roots. Healthy, functioning nodules should be pink on the inside. Seven to fourteen nodules/plant at first flower is considered adequate nodulation, but more is beneficial. A fully grown, properly nodulated soybean plant should have between 20 and 100 nodules.

Soybean plants secrete chemical signals (flavanoids) into the soil from the roots when they become N deficient. These signals are picked up by the rhizobia, which in return send a chemical signal back to the root. The signals sent back are called Nod factors. These Nod factors will cause root hairs to curl and pick up rhizobia and allows them to invade the root. Within 10-14 days of colonization a nodule will become visible.

Before the nodules start to supply adequate nitrogen to the leaves, soybeans often go through a period when leaves are light green or pale yellow. This stage is a normal phase in the development of a healthy crop and usually only lasts 1-2 weeks. Only in the absence of N (a pale looking crop) will the roots send the signal to the rhizobia to initiate nodulation. Once the nodules have established and start providing nitrogen, the leaves turn a dark green colour. This light green leaf phase is more pronounced in a dry spring. Usually by the third trifoliate stage, leaves turn a dark green colour.

Inoculants are not essential where a well-nodulated, dark-green soybean crop has grown in the past. If a producer is not certain that a previous soybean crop was well-nodulated, they should inoculate to avoid the possibility of poor nodulation. For proper nodulation to occur, a relatively high number of rhizobia must be present in the soil. Inoculates should be applied to every soybean crop on acidic soils (pH below 6.0), sandy soils, and fields with poor drainage that have been flooded for an extended period. Under these conditions, soybean soil rhizobia may have died out so adding fresh inoculant rhizobia will ensure good nodulation.

Pre-inoculants

Pre-inoculants are formulated to allow rhizobia to survive on seed which allows the seed to be inoculated months before planting. These pre-inoculants are usually applied as a commercial seed treatment and are compatible with many fungicides and insecticide seed treatments. The number of months a pre-inoculant is viable on the seed varies by product. Similar efficacy has been shown between pre-inoculants and inoculants applied immediately before planting.

On-farm inoculants

Good seed coverage is essential for maximum efficacy of an inoculant. Many inoculant products applied “on farm” at planting time use a sterile peat-based carrier or a liquid formulation. Sterile-carrier inoculants use a powdered peat base which is sterilized prior to the addition of the inoculant strain. Sterile-carrier inoculants carry much higher numbers of rhizobia when compared to older, non-sterile powdered peat. Non-sterile powdered inoculants run the risk of containing microbial contaminants. These microbial contaminants may compete with the rhizobia.

When applying “on farm”, apply inoculants at the base of a brush auger when loading the planter. There are also kits available that hang on the side of a truck, tote, or gravity wagon. Bridging can occur in the planter or build-up in the augers from over-application of liquid seed treatments or inoculants. Bridging can be reduced by simultaneously applying a low rate of peat.

When soybeans are grown on land for the first time, inoculation with soybean rhizobia is essential for high yields. Establishing a healthy number of root nodules on first-time fields can be challenging.

First-time soybean fields

To improve the chances of nodulation, the use of two different inoculants or at least two different lots of the same product is suggested. By using two products, the chance of a nodulation failure is reduced because the overall rhizobial population is increased. The likelihood of both products having low rhizobial counts is also lower. Although inoculant products are tested when they are packaged, poor handling, storage, or poor application may reduce the number of living rhizobia that are introduced at planting.

Fields with a history of soybeans

In Ontario trials, results indicate a 0.1 t/ha (1.3 bu/acre) yield increase by inoculating soybeans even in fields that have previously grown a well-nodulated soybean crop. In the absence of a soybean plant, rhizobia can survive for 7-10 years and in some fields over 50 years. Once a strain of rhizobia has become established in the soil, it will out-compete any new strain that is introduced on the seed. Studies have shown little success in replacing existing strains of rhizobia in the soil with newer, more-effective nitrogen fixing strains.

Nodulation failures

Specific seed treatments and liquid fertilizers can negatively impact inoculant performance. When using an inoculant, check the label to confirm how long the inoculant will be viable on the seed if applied with a seed treatment or mixed with a liquid fertilizer.

Manure or commercial nitrogen fertilizer applied to soybeans fields supplies a readily available source of N. Soybean will use this N prior to establishing nodules or used N supplied by the nodules. This is because biological N fixation is metabolically expensive to the plant, so the plant will first use soil available N. In fields with high soil N, nodulation may be delayed, but yields are usually still good as long as abundant soil N is available for the whole growing season. However, since N uptake does not peak until August, if soil N reserves run out an N deficiency may be observed late in the season, reducing yield.

When springtime soil temperatures are unusually cool, nodulation failures are common. Nodules can only form on new root hairs and root hairs are only present on new root growth. Sometimes roots will grow past where the inoculant was initially placed in the soil before nodulation occurs, resulting in a nodulation failure. This is more common in a cool spring. Soybeans are subtropical species which prefer soil temperatures above 25°C for optimal symbiotic activity. A root zone of at least 10°C to 15°C is critical for soybean nodulation and N fixation to occur. When soil temperatures are below 10°C, nodulation may not occur at all. Under extremely cool weather conditions, nodulation can be delayed until August.

Applying N fertilizer to fields with poor nodulation

See factsheet: Nitrogen