Tillage Options

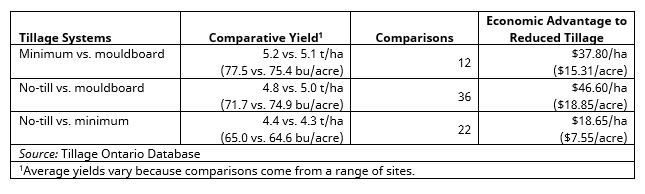

Cereal crops do not respond significantly to tillage. Research comparing the yield response of winter wheat to various tillage options demonstrated an economic advantage to reduced tillage with no significant yield difference among mouldboard plowing, minimum tillage and no-till systems, as shown in Table 4–1, Winter wheat yield response to tillage systems. While yields are not affected greatly by tillage systems, good seed-to-soil contact and soil moisture for germination are essential.

Table 4-1. Winter wheat yield response to tillage systems

The selection of a tillage system will impact other components in the system. The tillage method chosen must fit with factors such as fertility, insect and disease pressure and weed control for producing high-yielding, profitable crops. Risks associated with more intensive tillage in winter crops include greater potential for frost-heaving and increased risk of snow mould. Erosion is a concern with tillage in all crops.

There are several options for seeding cereals that include:

- no-till seeding

- conventional tillage

- frost seeding

- aerial seeding of winter cereals

- broadcast seeding

No-Till Seeding

Most winter wheat is grown using a no-till system. Yields in a no-till system are often equal to yields obtained in a conventional tillage system. No-till drills can follow the combine in the same field, which advances seeding date, therefore increasing yields. Winter cereals seeded in a no-till system are better able to resist frost heaving, as the plant anchors itself in firmer soil.

The success of a no-till system requires consideration of fertilizer management, drill capability and weed control. No-till cereals show more response to seed-placed starter fertilizer, especially phosphorus, compared to conventional tilled crops, refer to Corn Row Syndrome.

Seed-to-soil contact is critical for moisture uptake. No-till drills must be able to cut through residue and penetrate into hard soil to accurately place seed. Adding seed-firming wheels or plastic “hockey stick” seed firmers will help press the seed into the bottom of the seed trench, which will help increase seed-to-soil contact and improve seed depth uniformity. Weed control is critical in no-till systems. A burndown before planting ensures control of dandelions and other winter annual weeds and should be a standard practice. See the Ontario Crop Protection Hub, for burndown guidelines. To reduce disease incidence, use a fungicide seed treatment. For further information on seed treatments, see the Ontario Crop Protection Hub.

The addition or use of tillage coulters may show some benefit in a no-till system. Slight loosening of dry, hard soils allows for better, more rapid root development and growth. In a wet fall season, light tillage may speed soil drying and allow for planting into better conditions. These limited tillage methods should be used when dictated by soil conditions.

Conventional Tillage

Cereals have been grown for generations using the plow, disc and cultivator for seedbed preparation. Many spring cereals are still grown using conventional tillage. While this system works well, erosion concerns, fuel and labour costs, and limited yield response to tillage continue to shift acres into reduced tillage. The guidelines regarding seed-to-soil contact, planting into moisture and seeding depth accuracy are consistent with the no-till section. The tillage operations used in the conventional system replace the herbicide burndown.

Frost Seeding of Spring

Seeding spring cereals into frost can advance seeding dates and increase yields.

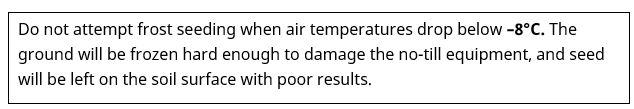

“Frost seeding” refers to no-till seeding cereals into a light frost in early spring. After the snow has melted and the frost is out of the ground, there are often several cold nights with below-zero temperatures. Seeding into this light frost avoids compaction or rutting, as the frost will support the tractor. It is not essential to close the seed trench when frost seeding, as the soil will naturally fall in and cover the seed as the frost comes out of the ground. Simply set no-till equipment to make a shallow seed trench, 2.5 cm (1 in.) and firm the seed into the bottom of the trench. Do not leave seed on top of the ground since stand establishment will be very poor. The window of opportunity for this method of seeding is short. Best results are generally achieved when cereals are seeded as the frost is just beginning to firm the soil, about -3 to -4°C, often near midnight. It is critical to stop as soon as frost begins to soften in the morning sun, as thawed soil will stick and plug equipment in as little as 15 m (50 ft) of travel.

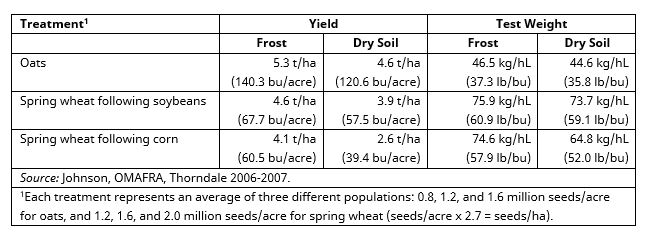

While this narrow window of opportunity may not occur every year, the increase in yield from early planting using this technique can be as much as 25%. Table 4–2, Frost seeding vs. seeding into dry soil of spring cereals, shows the yield and quality advantage of frost seeding. Frost seeding of winter cereals in the late fall or early winter have also been successful. However, in these situations it is critical that seed placement is at least 2.5 cm (1 in.) deep, and that yield expectations are realistic.

Table 4-2. Frost seeding vs. seeding into dry soil of spring cereals

Aerial Seeding Winter Wheat

Aerial seeding is most successful when seed is flown on before 10% of the soybean leaves have dropped. Soybean leaves will cover seed and help retain moisture for wheat germination.

Results from aerial seeding have been variable. The seed is extremely vulnerable to slug damage. Slugs feed on the germ of the kernel, which can severely thin or destroy the stand, particularly on headlands. The seed will appear to still be on the surface, as if waiting to germinate, but on closer examination, the damage to the kernel becomes evident. Reseeding of headlands after soybean harvest can help overcome this problem.

Photo 4-1. Slug eating germ out of seed

Photo courtesy of T. Meulensteen C & M Seeds.

The shallow root system that develops from aerial-seeded wheat is more prone to heaving injury and wind damage, refer to Depth of Seeding. In the spring, wheat plants will be attached to the soil by only one hair root. If this hair root breaks as plants twist with the wind, the plant dies.

With these inherent risks, yields from aerial-seeded wheat are often 10% lower than from drilled wheat, (limited on-farm trial data). Therefore, aerial seeding is not a standard practice. Where aerial seeding is attempted, increase the seeding rate to 5.0 million seeds/ha (2 million seeds/acre) to compensate for stand loss.

Broadcast Seeding

Broadcast seeding can greatly speed-up the planting process. It is important to get good seed-to-soil contact and a uniform seeding rate across the width of the spread pattern and between passes of the spreader.

Using airflow units is an effective way to achieve a uniform spread pattern. Till fields at a shallow depth, 7.5 cm (3 in.), twice, at right angles, to help prevent streaking in the seeding pattern, and then pack the crop to improve seed-to-soil contact.

Broadcast seeding produces an inconsistent seeding depth. Variable maturity and a 5%–10% reduction in yield are often the result. Increasing seeding rates by 10% will help compensate for the potential variability of broadcast seeding.