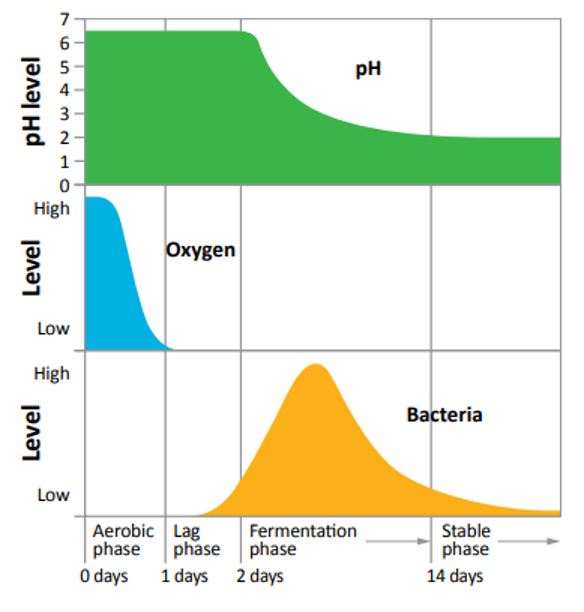

When forage is first put into a silo, conditions are aerobic (oxygen is present in the silage). Plant respiration and aerobic bacteria convert carbohydrates into carbon dioxide, water and heat, and use up the oxygen present. This phase should be as short as possible.

The silage then becomes anaerobic (without oxygen). The growth of anaerobic bacteria ferments sugars to organic acids (primarily lactic and acetic acid) and other products, including carbon dioxide, heat and water. This biological conversion from fresh plant material to fermented silage also results in the shrink or fermentation losses of dry matter and energy. A fast, efficient fermentation that is dominated by lactic acid bacteria (LAB) producing primarily lactic acid, reduces these losses to a minimum. In 2–4 weeks, the silage reaches a stable pH of 3.8 to 4.5, and all bacterial and enzymatic activity stops. Once this stable pH has been reached, further breakdown of nutrients and spoilage is prevented, and the silage will keep for extended periods of time, provided air (specifically oxygen) is excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The fermentation process

Good silage management is aimed at minimizing fermentation losses in dry matter and energy, commonly known as shrink. Shrink reduces both yield and nutrient quality. A poor or extended fermentation results from the following factors and will increase losses:

- slow filling

- poor packing

- poor covering

- improper harvest moisture, or

- lack of a suitable inoculant

When excessively wet material is put into a silo, moisture can squeeze from the silage. The seepage carries sugars and other nutrients out of the silo. In addition, seepage can lead to excessive corrosion of the silo walls and result in the possible collapse of the silo. Silo seepage can also cause fish kills if it enters a watercourse.

Species and maturity of the forage affect silage fermentation. Early-flowering legumes and vegetative grasses contain adequate sugars for fermentation by bacteria. Protein and energy values for livestock are optimal at this stage.

Grasses are easier to ferment than alfalfa and red clover as they contain a higher sugar content than the legumes; in fact, close to twice the amount. Mature legumes may lack sufficient sugar content for good fermentation. Wilting concentrates the sugars in the plant.

Fresh and fermented forages feed out differently. It is a good practice to have enough ensiled forage to allow a newly harvested crop to ferment for at least 2 weeks, although 6–12 weeks is better. This enables the forage to reach the stable phase of fermentation before it is fed.