By Joey Sabljic

Past articles in our Understanding Precision Agriculture series have focused on the main pieces — data collection, management zone creation, and prescription mapping — that form the foundation of a successful precision ag approach.

This month, we spoke with three growers who have been involved with the Precision Agriculture Advancement for Ontario (PAAO) project to hear about their experiences, challenges, and successes.

Zac Cohoon farms north of Port Perry, Ontario, where he grows corn, oats, soybeans, and hay. For Cohoon, the two, driving factors that got him invested in precision agriculture were labour and efficiency.

He points to GPS technology in the form of RTK (Real Time Kinematic) auto steer systems that have helped save labour, fuel, and time — all while creating an accurate base data set for management.

“Driving a big piece of equipment for a long period of time is exhausting mentally and physically — and when you don’t have to devote your full attention to driving straight or accurately, your data’s going to get a whole lot better,” he says.

By using an RTK system that plots his position accurately to within a few inches, Cohoon says that he has been able to nearly eliminate overlap across his field when planting and spraying. This helps him cut back on his seed and nutrient inputs, while collecting more accurate yield and elevation data.

“With auto-steer being a precision tool that really worked for us and was accurate, we were able to move into precision management, and collect geographical data to make maps,” explains Cohoon. “Now, we can look at soil types, elevations, test for soil fertility and overlap that information with our yield data.”

Instead of doing blanket applications of fertilizer, Cohoon says that his precision setup has evolved so that he can perform site-specific applications of fertilizer and seed.

Where Cohoon has run into challenges at times has been in getting his precision ag platform to work smoothly and seamlessly with his RTK system, and variable rate equipment.

“For me, driving and on-the-go planter management isn’t a problem, but as soon as we start looking at field-by-field or multi-field prescriptions, they just don’t have the computing power to do that,” he explains.

Cohoon adds that some of the platforms they use can only handle one prescription per SD card, which can get cumbersome when managing his 30-plus fields. He is, however, looking forward to new precision platforms that will allow him to remotely download and upload specific field prescriptions to his cab.

As for what’s on the horizon, Cohoon is working with his consultant to pull the most the valuable nuggets of information about his fields from all the data streaming out of his equipment.

“We have all this data, and we’re trying to get good answers from it — what’s relevant, what’s not relevant, and what do we need to focus on,” he says.

Cohoon hopes to be able to automate the process for developing prescription maps on a field-by-field basis to ensure he’s getting the maximum production for the least cost.

“Agriculture is about cost-control and being able to produce profitably. To me, that’s the real measure of a farmer’s ability to read his land and manage his enterprise,” he says.

USE WHAT YOU HAVE

Matt Porter is a precision ag equipment consultant with HUB International Equipment LTD., teaches agro-ecology at Fleming College and grows corn, soybeans, wheat, and canola in the Kingston area.

Porter consults with 22 growers — including Cohoon — in a wide geography that spans from Sarnia to Quebec.

He says one of the most common misconceptions he hears is, to actually do precision ag, growers must make a big-dollar investment in top-of-the-line precision equipment.

However, depending on that grower’s farm scale or budget, high-end equipment may not be the best route. But that doesn’t mean they may not already have a basic precision ag setup through the custom applicator that does their planting, spraying, and combining.

“I’ve spoken with a lot of guys who have a precision setup already without owning a thing — but you have to look for those partnerships,” says Porter.

Besides having high-end precision equipment, custom applicators will also collect yield and other data from their grower customers’ fields.

“A lot of growers either won’t ask or don’t know that they can ask for their yield data,” explains Porter. “But that is your information and you have a right to it.”

When hiring a consultant to perform soil tests of the their fields, Porter says that growers can also grab geo-reference points for the different soil samples and use that information to put together a basic soil map of their field.

Collecting data is one piece of the puzzle — but for growers to feel connected and engaged, Porter says that this data needs to be analyzed and presented in a way that speaks to the grower and their experience.

“I find that most farmers have this strong connection to their landscape — and when you couple harvest data and topography with a guy’s knowledge of his fields, we can go through and instinctively pull out different management zones,” he says.

But even with grower intuition, Porter contends that there are several, major knowledge gaps in Ontario — specifically in the more advanced computer, field surveying, and data visualization skills needed to interpret and map out raw data.

“We have people in cities that specialize in areas like geographic information system technology, but agriculture doesn’t have that strength right now,” says Porter. “That’s a huge gap and it can be a big mountain for a lot of growers to climb.”

However, what tends to be the biggest obstacle of all, according to Porter, is building a trusting relationship between consultant and grower — especially when many growers are used to having full control over every aspect of their operations.

“These growers — if they want to make something of all the data they’ve collected — they have to accept what they can and can’t do on their own and then trust you enough to take direction,” he explains. “There’s no smoke and mirrors here — it’s really hard work. And it can be difficult for some people to accept just how much work it is to get a project up and running.”

COMPATIBLE TECHNOLOGY

For growers wanting to work with a consultant and adopt precision ag practices, Porter says they need to take a hard look and decide whether they can commit to the full process.

“With precision ag, there’s no universal fit. You have to redefine the way you run your operation and make it habit,” he says. “You self-identify and look at your strengths and weaknesses, plan, and make it actual.”

COMMITTING TO THE PROCESS

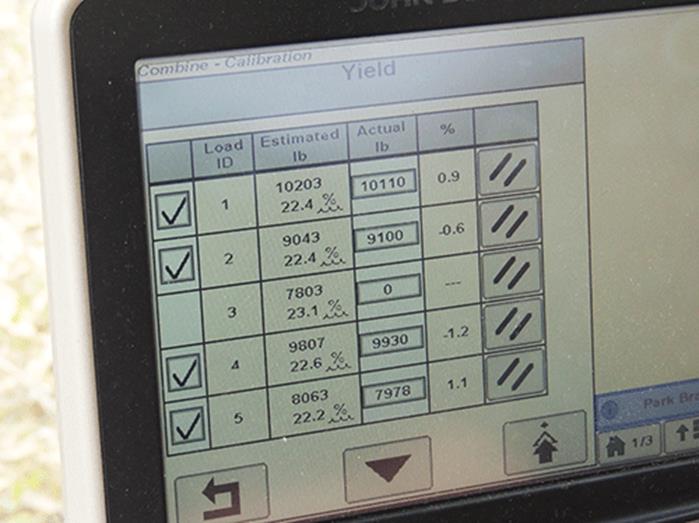

Mark Brock’s first foray into precision agriculture began with installing a yield monitor on their combine back in 1999. Since then, he’s been active in trying to improve their setup, trying out new technology, and expanding what can be measured.

Brock, chair of Grain Farmers of Ontario and director of District 9 (Perth), farms just outside of Staffa, Ontario, and took over the family cash crop operation in 2012. But it was shortly after coming home to farm full-time in 1997 that he began taking a hard look at precision ag equipment.

“I really started to see where we could make some improvements and how our farm was varied in terms of production, and I really wanted to quantify that,” says Brock.

The yield monitor, he explains was just the beginning. If anything, what they were seeing just sparked more questions.

“We were seeing our planter plant a little too much on the headland, or in a triangular piece of the field where the doubled seed population or spray application was actually causing a yield detriment,” he says.

As a result, one of the major equipment improvements Brock made was clutch control and spray section control systems. Brock also brought in variable rate controller systems that help him tailor his inputs based on his GPS coordinates, and then lay down accurate nutrient and seed prescriptions for the high, medium, and low-yielding areas of his fields.

As for which precision ag equipment he’s bringing into the field for the coming season, Brock says that his tractor, sprayer, and combine are all equipped with RTK-accurate auto-steer systems.

He also uses precision planting technology to ensure that he’s getting proper down force on the row units, putting down a precise seeding rate, and capturing data to record his applications.

Data collection, says Brock, is really what underpins his precision setup, with most of the data he collects focused on product usage (nutrient application and rates, and seeding populations) as well as yield and elevation.

“When I come back to analyze different areas, I can come back to seed count and nutrient application — or — going one step further, having soil test data in our system where we can see yield, soil tests, seeds, and nutrients applied to get a snapshot of what’s happened,” says Brock.

As for growers who may be on the fence about whether to dive into precision agriculture, Brock argues that there’s no time like the present.

“You can’t afford not to be in it — I think that’s just how our operations are going to evolve and that’s how we’re going to succeed in the future,” he says.

“In knowing that, choose to work with a service provider that can provide the support you need based on your skill set.”

This project was funded in part through Growing Forward 2 (GF2), a federal-provincial-territorial initiative. The Agricultural Adaptation Council assists in the delivery of GF2 in Ontario.

Precision Agriculture Advancement for Ontario: This article is part of a series dedicated to helping farmers understand and implement precision agriculture technology. It is based on research conducted by Nicole Rabe, Ian McDonald, and Ben Rosser at OMAFRA, in conjunction with Mike Duncan, Sarah Lepp, and Gregor MacLean at Niagara College.

For more on precision agriculture go to: www.gfo.ca/Research/Understanding-Precision-Ag. •