This article was written by Meghan Moran (OMAFRA Canola & Edible Bean Specialist) , Travis Cranmer and Dennis Van Dyk (OMAFRA Vegetable Crop Specialists)

There have been times growers and agronomists have asked, “What is this house fly-looking insect I am seeing in canola fields?” The flies were particularly abundant in some regions in 2017, and at the time it was assumed the flies were after the plentiful nectar in canola fields. In fact, flies are very important pollinators in nature. Flies are not as hairy as bees or as efficient at carrying pollen, but some are good pollinators (https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/animals/flies.shtml).

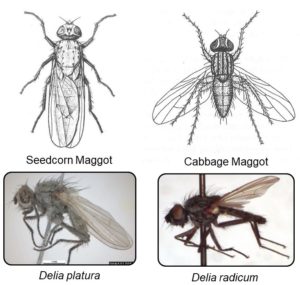

There are, however, several fly species that are pests of Brassicas. Ontario Brassica vegetable producers frequently battle with maggots (larval stage of flies) feeding on crop roots and robbing yield. The key players are Delia species, including the cabbage maggot (Delia radicum) and seedcorn maggot (Delia platura). The cabbage maggot can cause severe damage to all Brassica crops while the seedcorn maggot is a broad-spectrum pest that can target a wide range of crops. Adult cabbage and seedcorn maggot flies are about half the size of a house fly, grey to black in colour and have red eyes.

In the early spring, cabbage maggot flies emerge from the soil and the females lay small, white eggs about 2-10 cm below the soil line. Depending upon the temperature, eggs hatch 3-7 days later as larvae that immediately start boring into tap roots of susceptible Brassica crops. Small transplants and seedlings are most susceptible, and destruction tends to be worse during a cool and wet spring.

Cabbage maggots feed on the Brassica roots for approximately 3-4 weeks before they pupate in the soil. During that time, they eat the root hairs and create extensive tunnels throughout the roots, often killing or stunting the plant in the process.

A survey of 2890 canola fields in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba in 1995-1998 revealed that greater than 96% of fields showed evidence of maggot feeding (Soroka et al). In surveys in the late 80’s and early 90’s in western Canada, damage ranged from approximately 15% of plants showing some root damage, to 100% of observed plants showing extensive damage. Delia pests caused major constraints on canola production in the Edmonton area in the early 90’s.

While the impact in Ontario canola is unknown, cabbage maggot has historically been the most difficult insect pest of Brassica vegetable crops that growers encounter in Ontario. Root feeding in canola can lead to stunting, lodging, reduced branching and ultimately reduced yield. There are no established thresholds for cabbage maggot in vegetables or in canola. Insecticide options for certain Brassica vegetables are limited, but include the organophosphate chlorpyrifos and recently registered diamide cyantraniliprole (Verimark). Recent Ontario research has shown that many cabbage maggot populations have developed resistance to chlorpyrifos, and field experience with cyantraniliprolehas shown mixed results to date. Mitigation measures in canola may include heavy seeding rates or wide row spacings.

Flies and maggots of Delia species are difficult to identify without the use of a microscope. If adult flies are abundant in a field, or lodging and stunting are observed, check plant roots for maggots and evidence of tunneling through root tissue. It is good practice to check plant roots in all canola fields as incidence of clubroot disease is increasing across the province. Roots are an important part of crop health and can tell us a lot about what is happening above ground.

Contact Meghan Moran if root maggots are observed (meghan.moran@ontario.ca 519-546-1725). Collect some maggots if possible. Records of infestations and estimated damage levels will be kept to inform future research on management of Delia species in canola.

References:

Soroka, J. J., Dosdall, L. M., Olfert, O. O. and Seidle, E. 2004. Root maggots (Delia spp., Diptera: Anthomyiidae) in prairie canola (Brassica napus L. and B. rapa L.): Spatial and temporal surveys of root damage and prediction of damage levels. Can. J. Plant Sci. 84: 1171–1182.