Nitrates in Silage

Fast-growing crops can accumulate nitrates under dry weather conditions. This is most common in corn, but sorghums, sudangrass, millets, cereals, and Italian ryegrass can all accumulate high levels of nitrates and potentially cause nitrate poisoning in livestock.

Figure 1. Fast-growing forage crops like sorghum-sudangrass may accumulate nitrates under stressful growing conditions

Why are high nitrate levels a problem?

Nitrates (NO3-N) are converted to nitrites (NO2-N) in the rumen. Normally, the nitrites are quickly converted to ammonia (NH3-N) by rumen bacteria and is absorbed into the blood stream to be excreted with urine. When there are high levels of nitrates in the feed, the rumen microbes cannot keep up with nitrite production. The nitrites form methemoglobin in the blood, which reduces oxygen-carrying capacity. Signs of acute nitrate poisoning in animals include staggering, vomiting, laboured breathing, blue-grey mucous membranes, and death (typically within three hours). Chronic nitrate poisoning often appears as reduced weight gain, early-stage abortions, and premature births.

Nitrogen oxide gases (NO, NO2, N2O4) can form from the breakdown of nitrates during ensiling. High-nitrate forages can lead to greater releases which can quickly reach lethal levels. Nitrogen oxide gases are heavier than air, may be reddish or yellow-brown in colour, and have a bleach-like smell. Nitrogen oxide gases will accumulate in low-lying places, such as around the base of a silo or in the feed room below a tower. When ensiling forage that may have high nitrate concentrations, do not enter the silo for at least three weeks after harvest. If you must enter the silo to level or cover the silage, do it immediately after filling and leave the blower running while anyone is in the silo.

Which growing conditions elevate nitrates in crops?

There are several factors that are known to increase the risk of high nitrates in fast-growing crops and weeds:

- High soil nitrogen fertility. This could be from fertilizers, manure applications, legume plow-down crops or winter-killed alfalfa.

- Hail, frost, or prolonged cloudy weather. Under these conditions plant roots are taking up nitrates, but the leaves are unable to turn those nitrates into amino acids fast enough to prevent accumulation.

- Periods of dry weather followed by a rain. Nitrates move with soil water into the roots, so a flush of water after a dry spell will move lots of nitrogen into the plant. It takes 5-7 days for the crop to metabolize all that nitrate, so concentrations are highest during the first week after the rain event.

While the above conditions are good general guidelines, growing conditions in 2019 have added some complexity to the crop nitrate puzzle. In fields where smearing and compaction at planting have affected root development, the crop may experience moisture stress even under normal levels of precipitation. Fields showing symptoms of moisture stress may be at risk of accumulating nitrates following a rain that revives them.

What can producers do to manage nitrates?

Proper fermentation can reduce nitrate levels by 25-65%. It is important that the crop is at the correct moisture level for the silo being used (Table 1). If the crop is too wet or too dry it will not ferment properly, and the nitrate concentration will remain high. Baleage is generally too dry to ferment completely, so do not expect baleage to reduce nitrate levels as much as ensiling. Nitrate levels are stable in dry hay; if they are high at harvest, they will always be high.

Table 1. Correct moisture content for silage crops.

Nitrates accumulate most in the lower parts of the plant, so raising the cut height is commonly recommended to lower nitrate levels in the feed. However, if forage inventories are a concern, a better approach is to harvest at the normal cut height, allow the crop to ferment for at least 3-5 weeks, and then conduct a lab test for feed nitrates so it can be diluted if needed before feeding. Guidelines to interpret forage nitrate lab results are in Table 2 below.

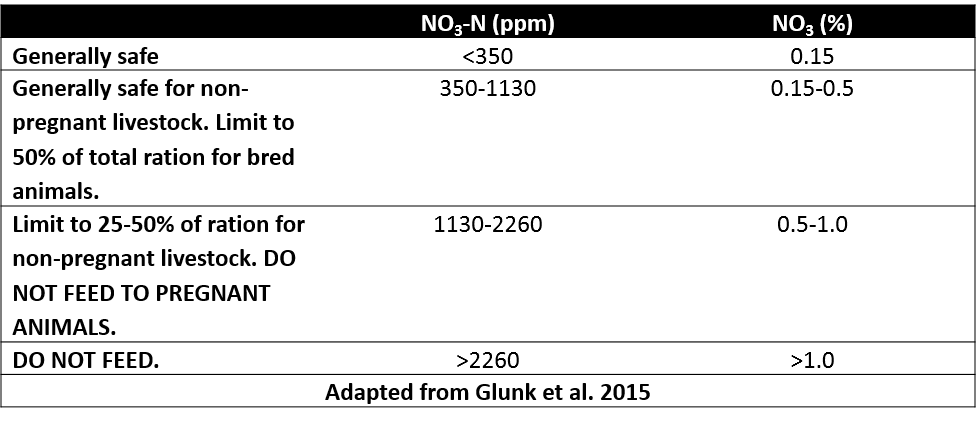

Testing the forage is the only way to know whether the level of nitrates may pose a problem. Most laboratories that conduct feed and forage analysis offer a nitrates test. Be sure the sample is representative of the feed, and it should be frozen to keep the nitrate levels from changing between the farm and the lab. The test results may report nitrates in a few different ways: as nitrate (NO3) or as nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N). These measurements may be expressed as a percentage or in parts per million (ppm).

Table 2. Guidelines for forage nitrate levels on a dry matter basis in cattle rations

To reduce the risk of acute nitrate poisoning, feed animals several meals a day, rather than one large one. Livestock fed once a day tend to eat a very large meal when the feed arrives; if the ration is high in nitrates, there is a large spike in their methemoglobin levels about eight hours later. Feeding twice a day results in ruminants eating smaller meals, and a smaller methemoglobin spike four hours after each meal.

Sources

Bagg, J. 2012. Potential nitrate poisoning and silo gas when using corn damaged by dry weather for silage, green chop or grazing. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs. Available from: http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/livestock/dairy/facts/info_beware.htm

Glunk, E., Oslen-Rutz, K., King, M., Wichman, D., Jones, C. 2015. Nitrate Toxicity of Montana Forages. Montana State University Extension. Available from: http://animalrange.montana.edu/documents/extension/nittoxmt.pdf

Yaremcio, B. 1991. Nitrate poisoning and feeding nitrate feeds to livestock. Alberta Department of Agriculture and Forestry. Available from: https://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/agdex851/$file/0006001.pdf

July 24-30, 2019 Weather Data